A

lifelong birder and retired physician, I grew up and began my practice

in New Jersey. After my career in the US Public Health Service, my wife

Mary Lou and I retired to the mountains of New Mexico, where we led

bird walks at Rio Grande Nature Center and the US Forest Service. The

cooperative rosy-finch feeding project we initiated at Sandia Crest has

developed into a major banding and research program. More recently we

moved to South Florida, where we are working to create a Bald Eagle

sanctuary to protect this species' first active nest in Broward County

since before DDT was banned. We migrate to a second home in northern

Illinois. I took up photography in 2008 and enjoy finding beauty in

birds and nature close to home.

"Of all living things, birds have most ensconced themselves in our

minds as being representative of all that is good about

nature." (George

Fenwick, founder of the American Bird Conservancy, in Birding:

July 2010)

How I Became a Birder

Anything

that flew or crawled was always a source of fascination for me. Things

had to have a name, and as a child my reading matter of choice had many

big pictures of animals, birds and insects. One time I was extremely

embarrassed by Peter, a kid who lived across the street. After I told

him that deer lost their horns every year he said “Deer don’t have

horns, they have antlers!” That was a crushing blow to my self

esteem—the pain lingers even now.

It

is hard to remember how I developed a passion for birds.

Perhaps

it is the freedom that they enjoy over us earthbound creatures. Of

course, their beauty, color, variety, and their accessibility make them

fun to study. Listing birds is somewhat analogous to collecting stamps,

satisfying some atavistic hunting instinct. The quest for new species

adds adventure to any trip, no matter what the purpose, and also causes

one to visit some unusual places. Swamps, landfills and sewage

treatment facilities rank high on birders’ “must see” locations.

Nowadays

I see my grandchildren naming the various species of dinosaur just as I

learned to name the birds. While knowing the names of birds provides

intellectual satisfaction, it also excites greater curiosity about

similarities and differences between the kinds of birds, not only in

their color, size and shape, but also in their habits, manner of

flying, their habitats, patterns of coming and going, and the marvels

of their survival.

Birders

have an undeserved reputation as eccentrics. At least, I think it is

undeserved, for I share their passion, and (of course) I am very

mainline and normal! There are sports nuts, compulsive stamp and beer

bottle collectors, golf and bridge addicts, and yet it seems that “old

ladies in tennis shoes” who happen to sport a pair of binoculars and

who get up early to look into treetops, oblivious to curious stares,

suffer public deprecation. Certainly, that was Mary Lou’s view. The

last thing she would think of doing was to go out and actually look for

birds.

My maternal grandmother, “Sweetheart,” (I gave Ella that name because

that is what she always called me) probably instilled some interest by

throwing bread out for the “chippies,” as she called the English

Sparrows (their proper name in those days). Then there was “Jenny” the

wren who occupied one of the bird houses on the trellis. I do not know

how Sweetheart came by that name, but later I found a wren named Jenny

in one of Thornton Burgess’s Bedtime Stories books..

I

collected bird pictures from Arm & Hammer Baking Soda boxes. My

first “real” bird book was a small format book by Chester A. Reed, Land Birds East of the Rockies (Doubleday, Page & Company, 1923).

There was a picture of a different bird on each page with descriptive

text next to it. As I identified each bird in the book, I penciled

across its picture in big block letters: “SAW.” That book was assigned

to the trash heap long ago, but I recently found another copy.

Another book that I really enjoyed was Birds of the South, (by Charlotte Hilton Green, published by UNC Press in 1933, almost a year before Roger Tory Peterson's first Field Guide)

which was given to me by Lou Fink, a family friend and scout leader who

authored a bird watching column in the local newspaper, The Rutherford

Republican. Its end papers sport some of my drawings, including a

Star-nosed Mole and a deer, and show my address as 164 Springfield and

telephone number “Rutherford-2-7392-M,” indicating that I was less than 8

years old when I defaced it. I did continue to use it, checking off the

table of contents for each species seen. I remember longing to see a

Mockingbird, unknown in the northeastern states at that time.

Mockingbirds would later expand their range and become quite common even

up into New England.

Birds of the South

included a table on which the reader could enter bird sightings. I

entered only one: “English Sparrow, August 29, in the garden eating weed

seeds.” I did not keep a more serious list until I was 13 years old

and in pursuit of a Boy Scout merit badge. This list began in the dead

of winter, 1948, and reflected a zeal for observing and recording that

has continued unabated for nearly 60 years to a present total of 564 US

and Canadian species, plus a couple hundred more seen on my few trips to

Hawaii and Latin America.

I still have my copy of the 1933 first edition of Roger Tory Peterson’s classic, A Field Guide to the Birds,

which Mom bought second hand for $2.75. This book, and its many later

editions, revolutionized the study of birds by allowing the observer to

separate them in the field rather than in the hand. Opera glasses and

binoculars replaced the gun barrel for bird study.

“Birding

is a fascinating, exciting, challenging game. It requires and

encourages ever-growing skill. It may involve us in great adventures

and wide travel, sometimes in difficult terrain. Seeking new birds to

check off on our life lists may draw us further into the lives of these

birds, challenging us to learn more about their life cycles, their

behaviors, and ecology; and as our ecological perspectives expand, we

may be stimulated to become more involved in conservation work, to

protect the habitats of the many species we enjoy.” (Burton S. Guttman, Birding, February 2004)

How

Mary Lou Became a Birder

As a kid, I

often thought how I would like to marry a girl who loved birds. As the

hormones raged and the demands of college and medical school

intervened, my birding activities dropped off sharply. I had turned

into a covert, “underground birder.” My criteria for an eligible wife

also changed. Of course, my Mom knew. She almost gave away my secret

when Mary Lou and I left on our honeymoon, way back in 1960. “Wait

until you see what Ken has in his suitcase,” she said. Of course, Mary

Lou had no clue and felt quite anxious that it might be chains and a

whip! She was most relieved to find binoculars and a bird

book!

As a kid, I

often thought how I would like to marry a girl who loved birds. As the

hormones raged and the demands of college and medical school

intervened, my birding activities dropped off sharply. I had turned

into a covert, “underground birder.” My criteria for an eligible wife

also changed. Of course, my Mom knew. She almost gave away my secret

when Mary Lou and I left on our honeymoon, way back in 1960. “Wait

until you see what Ken has in his suitcase,” she said. Of course, Mary

Lou had no clue and felt quite anxious that it might be chains and a

whip! She was most relieved to find binoculars and a bird

book!

Ironically,

Mary Lou would yet become an avid birder, but only after raising four

children. Our youngest child Glen, born in 1967, had severe

encephalopathy, a reaction to a measles vaccination at 18 months of

age. He lost the ability to walk and talk, and became totally

dependent. Mary Lou stayed home and cared for Glen his entire life,

until he died at 24 years of age. I retired soon after his death, and

we moved into the mountains of New Mexico. Mary Lou’s widowed mother

had become increasingly dependent, and she lived with us for several

years. Glen died on her 89th birthday (she was born the same day as Bob

Hope), and her condition deteriorated. After we moved to New Mexico she

finally had to be admitted to a nursing home in Albuquerque, where she

died at age of 94 on the day before Valentines Day.

During

the almost 30 years devoted to the care of our son and her mother, Mary

Lou had been pretty much home-bound. Only one of us would be able to

attend family events such as graduations, weddings and funerals.

Released from the burden of caregiver, Mary Lou was finally able to

travel.

She

always did appreciate the wonders of nature. We both loved hiking and

exploring the Great Outdoors when possible, but Mary Lou seemed to take

a more expansive and spiritual view of God’s creation while I was

staring at the Brown Creeper making its way up a tree trunk, trying to

see what it was finding to eat.

Once

retirement and release from the burdens of care-giving presented us

with more leisure and the opportunity to travel, we decided to try out

the Elderhostel program (now known as Roads Scholars). We did not know

what to expect, but our first Elderhostel, in the fall of 1996 on North

Carolina’s Outer Banks, was entirely enjoyable. We followed with

outdoors oriented Elderhostels on Catalina Island, Yellowstone, the

Navajo Reservation, and St. Mary’s, Georgia. The latter included

canoeing in Okeefenokee Swamp, which provided marvelous close

up wildlife viewing.

In

the spring of 1999, the notice of a Birding Elderhostel in Southeastern

Arizona caught my attention. I gingerly asked Mary Lou whether she

might want to go on it. Her reaction was predictable. All our previous

Elderhostels had not only introduced us to interesting places, but also

many fine fellow student-travelers whose company we really enjoyed. Why

should we go out before dawn looking for birds with a bunch of “weirdo”

bird watchers?

She

relented, but only on condition that she could study my field guide and

see if there were any birds she might enjoy viewing. As if she could

just pick and choose! I happily tutored her and provided lists of the

most likely sightings. She settled on only one bird that she just

really wanted to see: the Elegant Trogon. I certainly agreed with her

on that, as I had never seen one myself.

On

our way to our first Birding Elderhostel, we drove out to Arizona from

our home in New Mexico, staying one night in Silver City. Mary Lou

seemed single-minded in her quest for the beautiful but uncommon

Elegant Trogon. The next morning we stopped by Portal, Arizona and

visited Cave Creek Canyon, where the Elegant Trogon had been sighted a

few days before. We encountered birders who had seen it earlier that

day, but we did not succeed in locating one.

The

Elderhostel began on a Sunday afternoon and finished up with breakfast

on Saturday, May 8, 1999. We saw many interesting and new

birds, but we kept missing the Trogon. One day, on the grounds of Fort

Huachuca, our leaders split the group so some could go on a more

strenuous hike into Scheelite Canyon. We joined the mountain climbers

while the couch potatoes stayed back and walked Garden Canyon. We got

to see our first Red-faced Warblers and Spotted Owls, but a couple of

the “lazy folks” saw the Elegant Trogon down below!

We

spent the next day, Friday, May 7, 1999, away from the trogon haunts

and held little hope of ever seeing one. We did meet a visiting German

birder, who mentioned he had seen the Elegant Trogon at sunup that very

morning in Garden Canyon! Since we had a schedule to keep, and planned

to drive home right after breakfast the next morning, my hopes of

seeing a new "lifer" were dashed. I assumed Mary Lou did not care that

much about missing her “trophy” bird after all.

At

dinnertime, to my surprise, she said “Let’s get up early and try to get

out and see the trogon before breakfast.” I quickly assented, feeling

like Br’er Rabbit

in the Uncle Remus tale: "I don't

care what you do with me, Br’er Fox,” says he, "Just so you don't fling

me in that briar patch. Roast me, Br’er Fox,” says he, "But don't fling

me in that briar patch."

A

couple of other diners, who had also missed seeing the

trogon, heard Mary Lou’s surprising statement, and said they

wanted to join us. Mary Lou sternly told them that they had to be ready

to leave for Garden Canyon at 4:30 AM, or we would go without them.

Sure enough, we all gathered and I drove to the Fort. Just as

advertised, we not only saw the beautiful male Elegant Trogon, but a

female as well, and watched as she repeatedly entered and exited a

prospective nesting hole.

When

we got home, Mary Lou started logging her bird sightings, and has not

looked back since. On her “Elegant Trogon Day” I had already

accumulated sightings of 474 species over 51 years of birding in the

lower 48 states. Within less than 5 months, Mary Lou recorded her 100th

species, a Fox Sparrow, during a birding Elderhostel in Oregon. In the

meantime, I had seen only 3 “new” birds! The next year, after birding

only for 12 months, she bagged a Long-tailed Jaeger in Denali National

Park, Alaska (thanks to all the new birds we saw in Alaska, my list had

grown to 527 by then).

On

October 13, 2000 she hit 300 species with a Ferriginous Hawk in New

Mexico, and with a Green Parrot in the Lower Rio Grande Valley of Texas

in April, 2002 she reached the 400 species milestone. We

moved to South Florida in 2004, which provided a treasure

trove of new birds, and in 2007, a Grasshopper Sparrow brought her

North America ABA total to the coveted 500 mark—Mary Lou now has 507

species to my 576.

Having

a new birdwatcher in the family has been a real bonus for me. No more

sneaking out and apologizing for coming home late when the birding was

particularly good. Best of all, as Mary Lou ticked off each new life

bird, I shared with her the same sense of discovery. Some of her first

birds seem bigger than life. (Disclaimer-- my photography hobby started

much later, so these are recent images.)

Even

my old brain remembers her first meadowlark, almost as vividly as if it

were hanging on the wall:

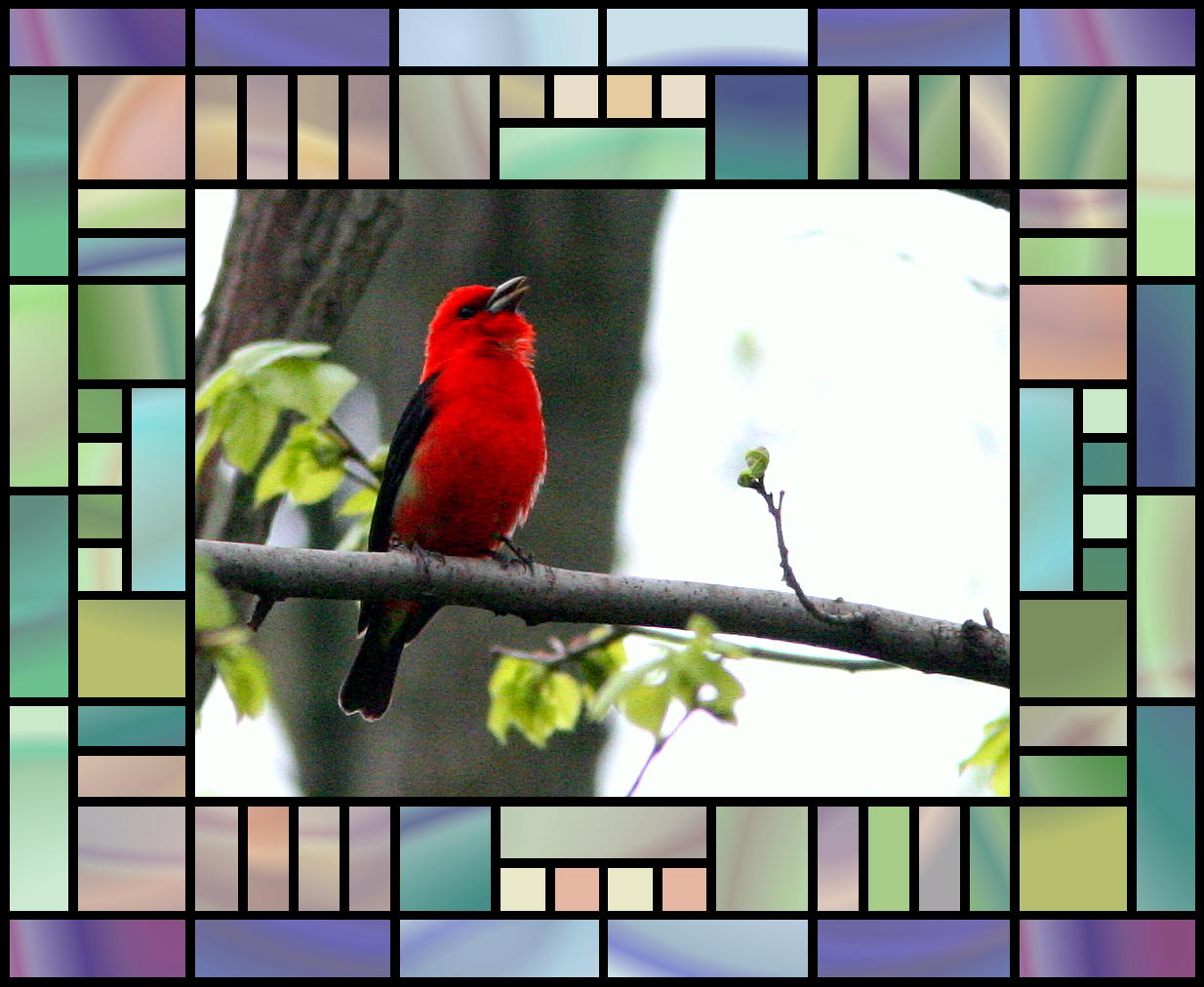

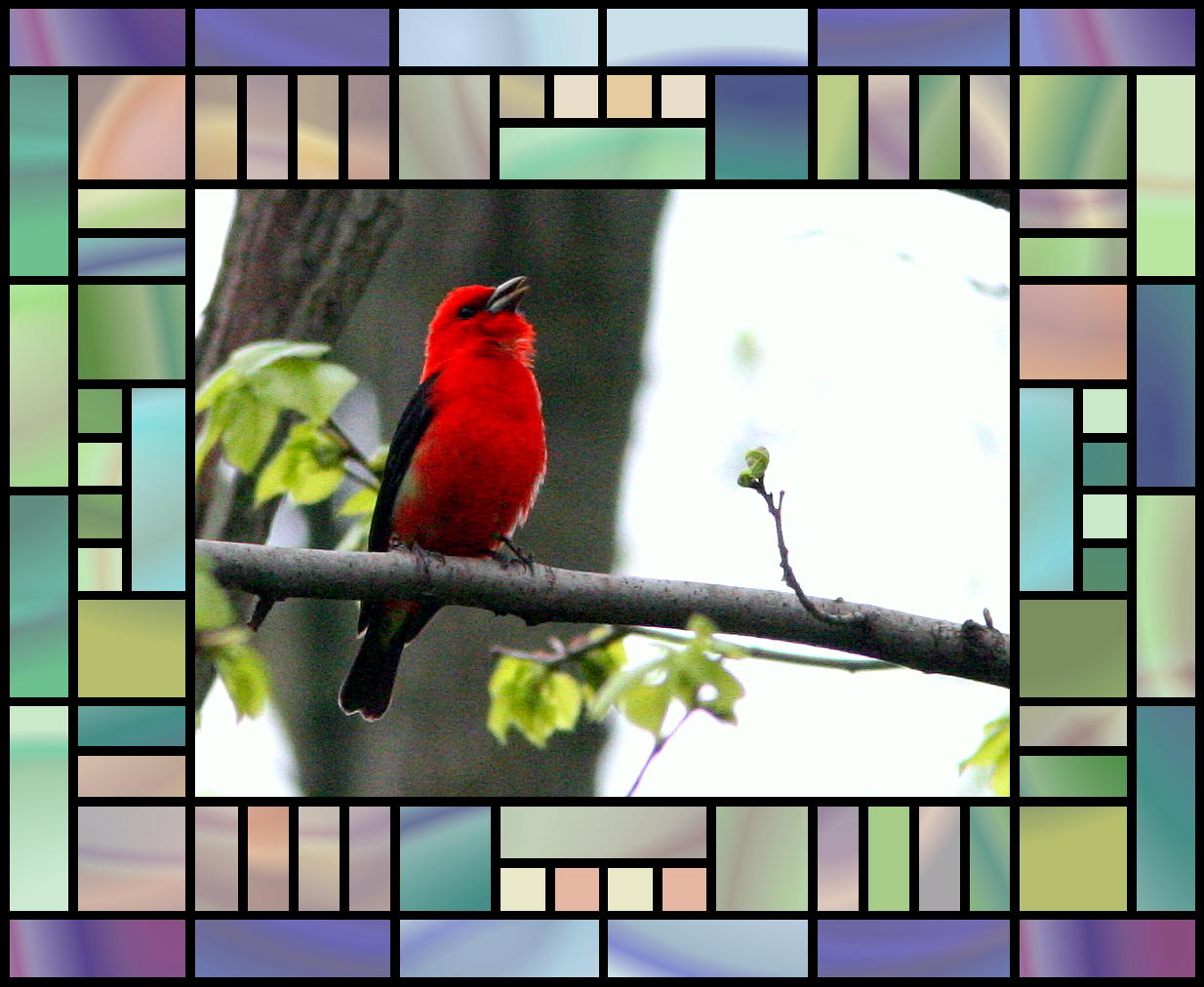

Scrupulously,

Mary Lou refused to "count" her first Scarlet Tanager because she could

not see the color of its tail:

And

of course, Mary Lou's favorite Florida bird is...

Seeking

our Signature Species

In a random but unknowing act of kindness, the construction worker

tossed his half-eaten sandwich on a snowbank along the road, and

returned to his job. A small flock of dark-feathered birds flew down

and shared the treat...

But, wait. I'm getting ahead of this story. I might have started with

"It was a dark and snowy morning when we drove to the top of the

world..." Instead, let's begin by recollecting our repeated futile

attempts to find rosy-finches on the top of Sandia Crest, 10,678 feet

above sea level, near our previous home in New Mexico. Several times

since moving there in 1993, Mary Lou and I would follow up on reports

of rosy-finch sightings on or near the Crest, only to be disappointed.

"It was a clear and cold morning..." in early December, 1999 when we

finally plugged three gaping holes in our life lists of birds we have seen. We rejoiced while

we watched about twenty birds, including all three rosy-finch species,

as they devoured the aforementioned bread crusts at the site of the

radio/TV transmission towers just across the parking lot from the Crest

House Restaurant and Gift Shop.

The next morning we repeated the 13 mile drive up the Crest Road,

carrying a supply of wild bird seed. Halfway up, snow started falling

and we drove slowly to the top. We scattered seed generously on the

snowbank where we had first seen the finches. They did not disappoint

us, as within minutes a dozen or more appeared along with some juncos

and they swarmed over the seed.

Upon revisiting a few days later we found that a snowplow had

distributed the seed all along the roadway, burying some, and exposing

the birds to a traffic hazard. This time we spread some seed on a

windswept snow-free area on the upper parking lot. Every week until the

end of February, 2000 we continued bringing seed, and birders

started noticing the rosy-finches. The next winter we resumed our

surreptitious feeding, and found that others were also scattering seed,

not only on the parking lot surface, but also on ecologically fragile

areas along the observation area at the top of Sandia Crest. We

publicized our concerns on the Internet, and this resulted in our

receiving dozens of inquiries about the rosy-finches. To manage the

requests for information, we set up the rosyfinch.com

website.

As Forest Service volunteers, we knew full well that wildlife feeding

violated the agency's policies, so we approached our friend Tom Duncan,

who was then the resident manager of Sandia Crest House. He talked to

Forest Service people and learned that the prohibition against feeding

applied only to "undisturbed" land; the Forest Service interpreted any

private leases or concessions within the National Forest boundaries to

be "disturbed" land, thus exempting the Crest House.

Tom erected a feeder only about three feet outside the main entrance to

the Gift Shop, and it immediately attracted rosy-finches. The trouble

was that they were frightened away every time someone entered or

exited, and they could not be observed from inside the building.

We engaged Central New Mexico Audubon, the US Forest Service, Crest

House management as well as a local bird seed supplier in an agreement

whereby three feeders were installed, to be maintained by Forest

Service volunteers. Spurred on by enthusiastic younger birders, most

notably the late Ryan Beaulieu and his friend, Raymond

VanBuskirk, Rio Grande Bird Research, Inc., managed by Steve

and Nancy Cox, expanded its operations to include weekly rosy-finch

banding sessions at the Crest House during the winter months. Read more

about Ryan's untimely death and how Raymond helped carry on his legacy

at the link to the June 2010 issue of Audubon Magazine on this

page.

After Gene Romero took over as manager of Crest House, the facility was

renovated to include an improved dining area with large picture windows

that provide a clear view of the deck feeder. Gene and his staff have

become avid watchers and protectors of the rosy-finches and, during the

warm months, myriad hummingbirds that frequent their feeders. Local

merchants donated feeders and seed, and Mary Lou and I coordinated the

feeding program, driving up about twice a week to tend them. We moved

away from New Mexico to Florida in 2004, and now Dave Weaver and his

spouse Fran Lusso carry on as co-coordinators of the feeding project.

For more information about the rosy-finches at Sandia Crest, see

my Birder's World article.

Since banding began in late spring of 2004 through the end of the winter of

2009-10, the team had accumulated a total of over 2200 newly banded

rosy-finches. The species mix of newly banded birds is

interesting. So far, 54% have been Black Rosy-Finches. The Brown-capped

species made up approximately 28%, and Gray-crowned Rosy-Finches

accounted for 18%. A little over half of the 432 Gray-crowned

Rosy-Finches banded were Hepburn's race, but of these 159 birds, most

(133) were banded during the two winters of 2006-07 and 2007-08. Detailed

results of banding are available here

Although we now have homes in Florida and Illinois, I remain a New

Mexican at heart. Mary Lou? Well, she certainly enjoyed most of our

eleven years of living at 7000 feet in the mountains of New Mexico, but

not the winters. As she says, she was born in December and hasn't

thawed out yet! However, we had not seen our five Texas grandchildren

since our 50th wedding

anniversary reunion in the Colorado Rockies in 2010, over a

year previously. We planned to fly to Amarillo for a "grandchildren

fix" this fall, but it took a bit of effort on my part to convince her

that we should fly home out of Albuquerque rather than Amarillo. After

all, the cheaper return air fare would offset the incremental cost of a

one-way car rental from Amarillo to Albuquerque. I also made sure that

the trip occurred after

the arrival of the rosy-finches to Sandia Crest. The first

ones usually appear around the first of November, but this year they

came in late. By November 9, no more than 6 Rosies had been seen at the

feeder.

We had a very nice visit with our son, his wife and their five

children, in Amarillo, Texas. On November 12, we drove west on I-40 to

New Mexico. As we approached Albuquerque, we could see the snow-capped

mountains of Santa Fe and Taos to the north, a promising sign, as snow

cover tends to concentrate the rosy-finches at the feeder. We arrived

at Sandia Crest around noon. It was a cold 29 degrees Farenheit, with a

brisk southerly wind with gusts to 50 miles per hour.

This is the view to the south from the deck of Crest House.

There had been a dusting of snow the previous day, but the deck of the

Crest House was clear. The feeder hangs over the far end of the

railing; a hungry Abert's Squirrel can be seen running along the top of

the rail towards it (click on photo to select larger views).

We saw a total of six Rosy-finches on November 12. Among them, we

identified three Black Rosy-Finches and one that looked like a

Gray-crowned. This is a Black Rosy-Finch.

This bird that we first thought to be a Gray-crown was more brownish,

but close examination of the photo reveals it to be an adult female

Black Rosy-Finch. The angle of light caused reflection that made the

bird look lighter than it really was.

An Abert's Squirrel was dominating the feeder, and we had to chase it

away repeatedly. The Rosies avoided the feeder when either the squirrel

or a Steller's Jay was present.

Mountain Chickadees shared the feeder...

...with Red-breasted Nuthatches...

...and the local Gray-headed race of the Dark-eyed Junco.

The next day, the forecast called for snow, but we ventured up Crest

Road again. It started to rain as we checked for Pygmy Nuthatches at

Doc Long Picnic Area near the base, and clouds enveloped the mountain.

We turned back, deciding to bird around Albuquerque. We returned to the

Crest on November 14, negotiating snow-packed areas on the road. Near

the top, the moisture from the clouds had condensed to form a thick

layer of hoarfrost on the trees.

Now there were flocks of up to 13 Black Rosy-Finches at the feeder.

Here, two are perched on a frosty branch.

Before the banders introduced a degree of sophistication into our

identification of the rosy-finches, we gave up on identifying many of

the hatch-year birds, especially early in the season, as all have buffy

brown tips on their contour feathers. At first we simply called them

"Rosy-Finch sp.," or "Buffies." Now we know to take a closer look at

the bases of the feathers. If they are black or very dark brown, and

the bird has a whitish crown, it is a Black Rosy-Finch. Immature

Gray-crowned Rosy-Finches have more cinnamon-brown feather bases. Male

Blacks, even immature ones, show rather extensive pink on their

underparts and wing coverts, while in females the color is very

subdued. Even adult Gray-crowned Rosy-Finches show relatively little

pink. This indeed is an immature (hatch year) female Black Rosy-Finch.

Note the hint of pink on her shoulders and lower belly.

Our disappointment at not being able to positively identify any

Gray-crowned Rosy-Finches was tempered by the appearance of the first

Brown-capped Rosy-Finch of the season. Note its lack of a light crown

and the more intense rosy undersides. A band from a previous season

confirms that it is an adult.

Although the temperature had dropped to 22 degrees, the winds had died

down, and photography conditions were much better than two days

previously. Somehow, this beautiful adult black-Rosy-Finch had escaped

the banding traps in previous years.

Though my fingers were about to freeze and drop off, I was able to get

a nice shot of a Mountain Chickadee against a natural background...

..and a Red-breasted Nuthatch in a typical pose.

I shot this photo of a Steller's Jay from inside the windows of the

Crest House. Staff had spread the seed around to allow the finches to

visit without being harassed by the jays.

Sandia Crest, just east of Albuquerque, New Mexico, is the most

accessible site in the world where all three North American rosy-finch

species can be seen at one time. We maintain the Sandia

Crest Birding FORUM, where you will find interesting

discussions on identification as well as updated sighting reports of

not only the Rosies, but also such more unusual birds as Clark's

Nutcracker, Red Crossbill, Cassin's Finch, Northern Pygmy-Owl and

American Three-toed Woodpecker.

Protecting a Neighborhood Bald Eagle Nest

With good reason, Alaska usually comes to mind at any mention of Bald

Eagles. Yet, it surprises some people to learn that, in the lower 48

states, breeding Bald Eagles are most numerous in Florida and

Minnesota. In 1990 there were 535 breeding pairs in Florida, and 437 in

Minnesota. The number of Florida breeding pairs rebounded rapidly to

1,102 pairs in 2001, then plateaued at 1,133 in 2005. In the meantime,

Minnesota's population climbed slowly at first, to 681 pairs in 2001,

then shot up to 1,312 pairs in 2005, surpassing the Florida population.

This

US Fish and Wildlife Service graph illustrates the recovery of breeding

Bald Eagles in the lower 48 states since DDT was banned in the early

1970s:

In an earlier post,

I described why the numbers of Bald Eagles in the more northern of the

lower 48 states increase during summer and early autumn, due not only

to newly fledged eaglets, but to the influx of more southern eagles.

The Florida birds perform an interesting "reverse" northward migration

after the breeding season. It is hypothesized that this contrary

behavior is caused by another sort of "migration," namely the vertical

movement of the eagles' main food source.

As Florida's lakes

heat up, the fish seek cooler temperatures in deeper water. Radio

tagging of Florida eagles has shown that many follow the cooler water

into the northeastern coastal states. Chesapeake Bay is a popular

summer and fall gathering place for the Florida population.Immature

birds tend to wander more widely than adults, with some even ending up

in Canada. Conversely, North America's northernmost Bald Eagles move

south with the approach of winter, seeking open water as the larger

lakes freeze up.

Alaskan

eagles are, on average, heavier than those in Florida and have longer

wings. I photographed this one in Soldotna, Alaska, along the Kenai

River:

We

have a particular interest in Bald Eagles, as we have been involved in

protecting a recently discovered nest in our south Florida

neighborhood. I serve on the Pembroke Pines Mayor's Bald Eagle

Sanctuary Steering Committee. During the first week of October, 2011,

Mary Lou and I were pleased to see that both members of the pair had

returned to the nest:

They were already rearranging the nest materials:

On

October 12, 2011, I photographed one of the pair at sunrise, flying

from the nest area in the general direction of the largest lake in our

subdivision:

On October 16, 2011, the female was sitting high on the nest...

...while her mate (judging by its slimmer build and slightly smaller size) roosted in a nearby Australian Pine:

We

first became aware of the local pair of eagles on December 4, 2007,

when I photographed them mating on the rooftop of a house just across

the lake from our home:

As

there had not been a record of an active Bald Eagle nest in Broward

County since several years before DDT was abolished in the early 1970s,

I reported the sighting on the Tropical Audubon Society's Web page, and

birders in neighboring Pembroke Pines had a general idea of where they

might be breeding. In March, 2008, Kelly Smith, a local middle school

teacher found the nest, located only about 150 feet from a busy

boulevard. It contained one nearly full-grown eaglet.

This photo of "P. Piney One" was taken by Kelly Smith on March 15, 2008 and is reproduced here with her permission:

This

pair of eagles has returned to the same nest each year, successfully

raising and fledging two chicks in 2009, three in 2010, two more

in 2011, a single chick in 2012 and two 2013 (one of these eaglets

disappeared at about 15 days of age). The nest is about 50 feet high in

an exotic Australian Pine tree with smaller trees blocking most of the

view, so we only get distant looks.

On December 11, 2008, both adults are shown sitting on the nest, only two days before the first of two eggs was laid::

Local

middle school students conducted a nationwide poll that chose names for

the two eaglets, “Hope” and "Justice:” They hatched on January 15,2009.

Here they are, squabbling with each other at exactly one month of age.

Hope, the older and larger, is on the left:

The

eagle nest attracted a great deal of attention, and crowds of up to 100

people came to see the antics of the eaglets, causing traffic hazards

as they stopped on the roadway and parked illegally.

The

Mayor took an interest in the nest, which is located on City of

Pembroke Pines property, and he announced his intention to declare the

site a City Bald Eagle Sanctuary, and took measures to protect both the

eagles and observers.The City has amended its planning documents to

pave the way for an ordinance that will provide safeguards against

disturbance of any eagle nest in the city. During the summer of 2011,

major resurfacing of the roadway and construction of a sidewalk were

suspended in the area of the nest during the eagles' breeding season

(May 15 - October 1).

I

photographed these three eaglets on March 2, 2010. The Middle School

students' poll resulted in them being named Chance, Lucky and Courage.

All three fledged successfully:

The eagles returned in October, 2010 to refurbish the nest, and eggs were laid around December 11. ( * See end note about how we estimate the time of egg laying and hatching). On January 23, 2011 at the age of about 9 days, this chick was first seen, peering over the nest rim:

Here, it waits as its parent tears off a bit of food. A younger sibling was not yet visible from the ground:

The Parent eagle feeds the chick :

This

was about as good a view we could get from 150 feet. Vegetation now

makes viewing much more difficult. Plans for a nest camera did not

materialize:

Here is the older of the two eaglets, on February 3, 2011. Much of her natal down has already disappeared:

At one month old, on February 15, 2011, the down had been reduced to a fuzzy cap:

Less

than two weeks later, on February 27, 2011, the eaglets looked almost

as large as adults. We called them "P. Piney Seven & Eight."

Bald Eagles exhibit sexual dimorphism that starts when they are

nestlings, with the females usually considerably larger than males. PP

7 is the larger and was presumed to be a female:

At

two and a half months of age on March 23, 2011 they were exercising

their wings, preparing for their first flight, which usually occurs

when they are between 10 and 12 weeks old. PP7, on the right, has more

white underneath than her younger brother:

On March 30, 2011, we found PP8 alone in the nest; PP7 had flown off, but returned within three days to be fed:

On March 30, PP8 was "helicoptering," hovering in place up to a foot off the ground:

Here,

on April 3, 2011, my last shot of PP7 shows her roosting in a tree next

to the nest. PP8 was flying back and forth on branches in the nest tree:

As

of this writing, in March, 2013, this pair of eagles is known to have

hatched out at least eleven chicks, of which nine were confirmed

to have fledged successfully.

*In

estimating the timing of the laying of eggs and hatching of the

eaglets, we must depend upon clues from changes in the behavior of the

adults. The onset of incubation coincides with the laying of the first

egg, which is when we suddenly see one of the pair down deep and

immobile in the nest. Hatching is a time of excitement, as the parents

shift position frequently, peer down into the nest, and they start

bringing in prey and tearing off bits to feed the tiny chick. The

adults also sit a bit higher in the nest after the first egg hatches,

supporting themselves on their wings to form a "tent" to shelter the

chick and yet provide warmth to any eggs that have not yet hatched.

Volunteer

nest observers share their sightings and photos, and respond to queries

in the Pembroke Pines Eagle Nest Watch FORUM here, which includes a

link to spreadsheets that document observations over the past three

breeding seasons .