"Sandpiper" meant those

little robotic things that chased the foam from the breakers up onto

the dry sand, and quickly reversed course to follow the foam back into

the sea. At first I thought that sandpipers had eternally wet feet.

Eventually I learned that this does not hold true all the time, and

that some species are quite comfortable away from water for much of

their lives.

Our

two Illinois granddaughters are visiting, and birding must take a back

seat to grandfathering. We finally have gotten out the past three

mornings while they are away visiting the theme parks in Orlando. This

morning, pouring rain is allowing me some computer face time. As is our

habit, we got out before sunrise. This is the view looking back east,

towards the gate where we enter the gravel road that leads into the

wetlands. Welfare checks on the heron rookery have found them doing

well, with eggs in five Yellow-crowned Night-Heron nests and one Green

Heron nest. A sixth Yellow-crowned nest is difficult to see, but it

appears to have been abandoned before any eggs were laid. We suspect

there is a second Green Heron nest but is is probably deep in dense

vegetation.

The path that

leads to to our favorite birding patch is only a few paces outside the

entrance gate to our subdivision. However, we must reach the gate by

walking in front of about two blocks of residences. Clothed in our

rugged garb, we accept quizzical stares from passing motorists as they

bring their kids to school or head for the office, all dressed up. We

are often recognized as birders, and have acquired some legitimacy by

answering questions from neighbors, such as “Did you notice that a lot

of baby white cranes [translation: Snowy Egrets] have just joined their

parents [translation: Great Egrets] along our lake?” Here in

Florida we must pay special attention to protection from sun and

insects. Sensible wide-brimmed hats, trousers tucked into socks and

long sleeves on the hottest of mornings make us stand apart on the

fashion scene. (No wonder Mary Lou regarded all birders as rather

eccentric folk– until she became one herself! See: “A Valentine for my

Favorite Birdwatcher“)

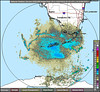

Returning from

Illinois this past Thursday, our aircraft passed eastward over the Fort

Lauderdale airport and took a long downwind leg over the ocean. This

meant that the wind was blowing in from the Everglades, and we could

expect rising temperatures and a plague of mosquitoes until the

easterly sea breezes returned.

The

unsettled air produced a lovely sunrise, but bad as the mosquitoes,

heat and humidity have been, other concerns are keeping us from going

afield...

Alas, we are

leaving our second home in northeastern Illinois to return to Florida,

just at the start of warbler migration. Yesterday Kane County Audubon

Society sponsored its monthly “Scope Day” at Nelson Lake/Dick Young

Forest Preserve, only about a mile from our condo. Although I obtained

not a single decent shot of any of the Common Yellowthroats, American

Redstarts, Magnolia Warblers and Black-throated Green Warblers we

sighted, the arduous 3 1/2 mile walk around the lake made for a most

enjoyable morning. We logged over 60 species.

The group

included a nice mix of experienced and casual local birders, as well as

visitors from out of state. They gathered on the east viewing platform

to scope out herons and ducks...

Travel, first

to Alaska, and more recently in Europe, has occupied much of my past

two months. Before leaving for a visit to Spain and a western

Mediterranean cruise earlier this month, I wrote three blog posts and

scheduled them for publication on consecutive Saturday mornings. I now

have to catch up and tell about the varied results of my recent hunting

experiences. The great painter John James Audubon was known to

cook and eat many of the birds he collected.

“Although he would shoot the

birds for sport, he also shot them in order to paint their features. In

his mission for new specimens, Audubon would shoot a minimum of a

hundred birds each day... ”

We enjoyed a scenic four hour drive from Homer to

Seward, first retracing our route north and westward on Sterling

Highway (Alaska #1). The early King Salmon run bypasses Soldotna for

some reason, but upstream at Sterling, fishermen were lined

shoulder-to-shoulder along the banks of the Kenai River. Joining Alaska

#9 southward, we were treated to the rugged beauty of the Chugach

Mountains. This

is a continuation of the narrative of our Alaska journey...

Review:

The Crossley ID Guide: Eastern Birds

Richard Crossley

Princeton University

Press

When I first picked up

this book, I was surprised at how hefty it was. Like so many other

birders, I saw the pre-publication press releases and the author’s

video preview. The computer screen images of birds in multiple poses

and at various distances were very appealing. I did not give much

thought to the fact that displaying 640 of these plates in a readable

format would require lots of large pages. Indeed, the book measures

about 8 x 10 inches and its 544 high-quality heavy pages produce a

volume that is 1 1/2 inches thick and feels like it weighs about 4

pounds. This is not a field guide, nor is it meant to grace the

cocktail table. Rather, it is a unique tool for learning how to better

identify the birds. It includes an unprecedented 10,000 individual bird

images, all from Crossley’s own collection, except for a handful

contributed by other photographers.

Soon after returning from from Alaska to our

second home in Illinois, I took a break from editing and reviewing the

photos from the trip. Illinois weather had been quite variable, from

cool and rainy to hotter than Florida. Our first stop was at Aurora

West Forest Preserve, only a couple of miles from our condo. Our target

bird was the Clay-colored Sparrow that nested there last year. We had

no luck in finding the sparrow, but it was a delightful morning full of

color and sound.

An Indigo Bunting sang a variant song from the

top of a tree. Mary Lou and I had heard this same bird before we left

for Alaska. Instead of the usual series of coupled warbling notes, this

bird repeated two wheezy phrases that sounded like “Wree-Wree,

Wree-Wree…” etc. It definitely meant to be singing, not sounding call

notes.

Last week, while I was still in Illinois, I received an

e-mail from Michael Fullana, a professional photographer who lives near

our Florida home. He had seen one of my Bobcat photos on the Internet

and was surprised to learn that they could be found so nearby. I gave

him detailed instructions and within a day or so he was out before dawn

in the wetlands next to our subdivision. He was able to get two photos

of a very handsome Bobcat a little after sunrise. Michael’s

photo was to die for, so I planned to get out early myself on the first

morning that we did not have medical and dental appointments. Today we

finally had no other obligations or early rain.

After reading my past three blogs about our

Alaska trip, our son-in-law, who accompanied Mary Lou and me in the

32-foot RV with our daughter and their two children, was only

half-joking when he commented that I wrote volumes about the birds, but

only a few lines about my loving family! The truth is, we spent much

more time having fun together than we did looking for birds. But my

blog is usually about birding and photography, and when it isn’t, I

publish a disclaimer.

The route from Soldotna to Homer was direct and only about

75 miles. Approaching from the bluffs north of the city, we could see

Homer Spit arching out into Kechimak Bay. Our objective was Heritage RV

Park, which turned out to be a very nice place for our two-night stay.

At

our South Florida home, we are lucky to live on a lake that is almost a

quarter of a mile wide, in back of our home. This gives us a chance to

practice identifying the waders that appear on the opposite shore,

before reaching for the binoculars to confirm our impressions. Overall

size, shape and behavior can be more reliable than color at such a

distance. Taking inspiration from Jerry Liguori's Hawks at a Distance,

I found some illustrative examples in my photo collection.

It seems essential

to my well-being for me to get out at least a couple of days a week.

"Out" doesn't mean our regular, and enjoyable, early morning "power

walk." No, I'm referring to what comes next when chores and other

obligations do not interfere-- a walk on the wild side. Here in South

Florida we have several favorite places within walking distance or a

few minutes' drive. One particular morning last week, I got out quite

early.

It seems essential

to my well-being for me to get out at least a couple of days a week.

"Out" doesn't mean our regular, and enjoyable, early morning "power

walk." No, I'm referring to what comes next when chores and other

obligations do not interfere-- a walk on the wild side. Here in South

Florida we have several favorite places within walking distance or a

few minutes' drive. One particular morning last week, I got out quite

early.

Mary

Lou and I observed our local Bald Eagle nest from about 8:00 to 8:45 AM

this morning. The female was feeding the eaglets when we arrived. She

flew off the nest after about 10 minutes and roosted in the melaleucas

for the rest of the time we observed them.The chicks were up and alert

for a minute or so, then rested down low in the nest. It’s getting hard

to tell the two largest apart– I thought they were arranged (left to

right) from oldest to youngest, but now I’m not sure. The middle

appears taller, but the left one seems to have less down on its head.

If the second is a female, she will be larger than an older male before

fledging. I will use this photo on the “Name the Baby Eagles” poll page

unless someone comes up with a better one and will give me permission

to post it there.Only about 5 minutes later, the male adult (his

distinguishing brown feather tail tip was better seen on another photo)

flew to the nest. Upon arriving, he either dropped the prey as he began

to land, or saw that there was no food in the nest, as he never entered

the nest and quickly dropped down and away. He returned only about 5

minutes later with prey.

Mary

Lou and I observed our local Bald Eagle nest from about 8:00 to 8:45 AM

this morning. The female was feeding the eaglets when we arrived. She

flew off the nest after about 10 minutes and roosted in the melaleucas

for the rest of the time we observed them.The chicks were up and alert

for a minute or so, then rested down low in the nest. It’s getting hard

to tell the two largest apart– I thought they were arranged (left to

right) from oldest to youngest, but now I’m not sure. The middle

appears taller, but the left one seems to have less down on its head.

If the second is a female, she will be larger than an older male before

fledging. I will use this photo on the “Name the Baby Eagles” poll page

unless someone comes up with a better one and will give me permission

to post it there.Only about 5 minutes later, the male adult (his

distinguishing brown feather tail tip was better seen on another photo)

flew to the nest. Upon arriving, he either dropped the prey as he began

to land, or saw that there was no food in the nest, as he never entered

the nest and quickly dropped down and away. He returned only about 5

minutes later with prey.

Birds

and birders flock to water treatment plants. My first experience with

one was the sewage pond at Fort Bliss in El Paso, Texas. It was a green

oasis in the otherwise arid desert, chock full of shorebirds. It

smelled to high heaven! This one has a modest name, Stormwater

Treatment Area Number 5, STA-5 for short, managed by the South Florida

Water Management District, and located south of Lake Okeechobee in

no-man’s-land of Hendry County. In the middle of the sugar cane fields,

STA-5 consists of four large shallow ponds that occupy an area of eight

square miles. Audubon of

Southwest Florida calls it one of the best birding spots in

all of Florida.

Birds

and birders flock to water treatment plants. My first experience with

one was the sewage pond at Fort Bliss in El Paso, Texas. It was a green

oasis in the otherwise arid desert, chock full of shorebirds. It

smelled to high heaven! This one has a modest name, Stormwater

Treatment Area Number 5, STA-5 for short, managed by the South Florida

Water Management District, and located south of Lake Okeechobee in

no-man’s-land of Hendry County. In the middle of the sugar cane fields,

STA-5 consists of four large shallow ponds that occupy an area of eight

square miles. Audubon of

Southwest Florida calls it one of the best birding spots in

all of Florida.

Similar

to domestic sewage settling ponds, STA-5 receives waste water and

allows impurities to precipitate out and serve as food for millions and

billions of trillions of microorganisms, algae and water plants. But

unlike urban sewer plants, the source of the water is runoff from

Florida’s generous summer rains, and the waste is agricultural effluent

from the many farms upstream. Fertilizers, pesticides and herbicides

dissolved in the runoff are captured and stored before purified water

is released into the Everglades. Phosphorus is the main culprit. The

Everglades are historically poor in nutrients, and phosphorus

stimulates the growth of cattails that overrun the sawgrass that

normally carpets the River of Grass.

When

walking in wild places, it is best to expect the unexpected.

More often than not, whether searching for a goshawk in the mountains

of New Mexico, the Red-headed Woodpecker in my favorite birding patch

in Illinois, or a Cottonmouth in the wetlands next to my Florida home,

my quest eludes me. Therefore, I keep an open mind and just wait for

each new day’s surprise. By South Florida standards, yesterday

morning was another in a string of unusually cold days. The temperature

was in the low forties, and a brisk breeze blew in from the north.

Insects were inactive in the cold. Tree leaves and grasses were

swaying, making it difficult to detect subtle movements that might

betray small creatures hiding in the foliage. Not a good day for

finding birds and butterflies.

When

walking in wild places, it is best to expect the unexpected.

More often than not, whether searching for a goshawk in the mountains

of New Mexico, the Red-headed Woodpecker in my favorite birding patch

in Illinois, or a Cottonmouth in the wetlands next to my Florida home,

my quest eludes me. Therefore, I keep an open mind and just wait for

each new day’s surprise. By South Florida standards, yesterday

morning was another in a string of unusually cold days. The temperature

was in the low forties, and a brisk breeze blew in from the north.

Insects were inactive in the cold. Tree leaves and grasses were

swaying, making it difficult to detect subtle movements that might

betray small creatures hiding in the foliage. Not a good day for

finding birds and butterflies.

My first stop, as usual, was a

patch of mostly exotic shrubbery at the edge of our subdivision,

happily left undisturbed by the landscaping contractors. It was

decidedly “un-birdy.” Even the usually reliable mockingbirds and

gnatcatchers seemed to have shunned it. Then I saw a flash of bright

red in a weedy patch just to my left. Too small for a cardinal. It had

to be a male Painted Bunting, the only other bird I could expect to see

sporting that color. So far, I had never seen a male bunting here, and

that would be a nice find. This turned out to be the first of two

surprises.

Observers

of our local Bald Eagle nest have noted some interesting

behaviors. These are personal discoveries. They gain insights into the

lives of these magnificent birds, and it matters not that their

findings are not new to science. We learned that,

unlike

many other birds, the eaglets do not abandon the nest after learning to

fly. After their first flight, the adults coaxed the fledglings back to

the nest with food. The youngsters returned to be fed at the nest daily

for two full months. Sometimes one or both would follow the parent as

it carried prey back to the nest.They

witnessed interspecific competition, as, for example, when an Osprey,

probably distressed after an eagle had stolen its fish, chased the

larger raptor back to its nest. The eagle did not endanger its chicks

by allowing its pursuer to make a close approach. Instead, the eagle

flew off until it eluded the Osprey, then returned to feed the fish to

the eaglets. They saw how smaller birds will harass the eagles

that roost in their territory by “mobbing” them until they depart. For

a video and my photos of grackles ganging up on an immature

eagle,

Observers

of our local Bald Eagle nest have noted some interesting

behaviors. These are personal discoveries. They gain insights into the

lives of these magnificent birds, and it matters not that their

findings are not new to science. We learned that,

unlike

many other birds, the eaglets do not abandon the nest after learning to

fly. After their first flight, the adults coaxed the fledglings back to

the nest with food. The youngsters returned to be fed at the nest daily

for two full months. Sometimes one or both would follow the parent as

it carried prey back to the nest.They

witnessed interspecific competition, as, for example, when an Osprey,

probably distressed after an eagle had stolen its fish, chased the

larger raptor back to its nest. The eagle did not endanger its chicks

by allowing its pursuer to make a close approach. Instead, the eagle

flew off until it eluded the Osprey, then returned to feed the fish to

the eaglets. They saw how smaller birds will harass the eagles

that roost in their territory by “mobbing” them until they depart. For

a video and my photos of grackles ganging up on an immature

eagle,

VISIT

ROSYFINCH.COM

Contact

Ken The first

time I heard a Florida birder talk about finding birds in a certain

"hammock," I almost wanted to correct him. Up east, the only hammocks I

knew were made of canvas and slung between two posts. I thought he

meant to say "hummock," a word that I first heard used by a farmer, who

pointed to a hill out in the middle of his hayfield that was too steep

to mow and had gone over to shrubs and trees. Of course, I've since

learned that "hammock" has a very specific meaning in any discussion of

Everglades ecology. From the ground, a hammock indeed looks like a

"hummock," a tree-covered hill that rises high above the surrounding

Sawgrass prairie. Hammocks are scattered throughout the Everglades, but

they are actually quite level, and only a foot or so above the high

water mark. It is the trees themselves that rise up in a graceful

mound. In the dry soil, hardwoods of many kinds flourish, draped with

ferns and air plants: mahogany, oak, maple, hackberry and gumbo limbo,

as well as native palms. Cocoplum, commonly used as a hedge or small

shrub in residential neighborhoods, grows to tree size. Hammocks serve

as refuges for more terrestrial creatures such as bobcats, panthers and

raccoons.

The first

time I heard a Florida birder talk about finding birds in a certain

"hammock," I almost wanted to correct him. Up east, the only hammocks I

knew were made of canvas and slung between two posts. I thought he

meant to say "hummock," a word that I first heard used by a farmer, who

pointed to a hill out in the middle of his hayfield that was too steep

to mow and had gone over to shrubs and trees. Of course, I've since

learned that "hammock" has a very specific meaning in any discussion of

Everglades ecology. From the ground, a hammock indeed looks like a

"hummock," a tree-covered hill that rises high above the surrounding

Sawgrass prairie. Hammocks are scattered throughout the Everglades, but

they are actually quite level, and only a foot or so above the high

water mark. It is the trees themselves that rise up in a graceful

mound. In the dry soil, hardwoods of many kinds flourish, draped with

ferns and air plants: mahogany, oak, maple, hackberry and gumbo limbo,

as well as native palms. Cocoplum, commonly used as a hedge or small

shrub in residential neighborhoods, grows to tree size. Hammocks serve

as refuges for more terrestrial creatures such as bobcats, panthers and

raccoons.

“West Pines Soccer

Park and Nature Preserve” sounds like a contradiction in terms, akin to

“Joe’s Barber Shop and Fine Dining.” Located near our Florida home in

neighboring Pembroke Pines, its extensive soccer fields share a border

with a fragmented Water Conservation Area. Suburban housing nearly

envelops the entire complex, yet it is an unexpected little patch of

protected natural habitat.

“West Pines Soccer

Park and Nature Preserve” sounds like a contradiction in terms, akin to

“Joe’s Barber Shop and Fine Dining.” Located near our Florida home in

neighboring Pembroke Pines, its extensive soccer fields share a border

with a fragmented Water Conservation Area. Suburban housing nearly

envelops the entire complex, yet it is an unexpected little patch of

protected natural habitat. It seems essential

to my well-being for me to get out at least a couple of days a week.

"Out" doesn't mean our regular, and enjoyable, early morning "power

walk." No, I'm referring to what comes next when chores and other

obligations do not interfere-- a walk on the wild side. Here in South

Florida we have several favorite places within walking distance or a

few minutes' drive. One particular morning last week, I got out quite

early.

It seems essential

to my well-being for me to get out at least a couple of days a week.

"Out" doesn't mean our regular, and enjoyable, early morning "power

walk." No, I'm referring to what comes next when chores and other

obligations do not interfere-- a walk on the wild side. Here in South

Florida we have several favorite places within walking distance or a

few minutes' drive. One particular morning last week, I got out quite

early.

Birds

and birders flock to water treatment plants. My first experience with

one was the sewage pond at Fort Bliss in El Paso, Texas. It was a green

oasis in the otherwise arid desert, chock full of shorebirds. It

smelled to high heaven! This one has a modest name, Stormwater

Treatment Area Number 5, STA-5 for short, managed by the South Florida

Water Management District, and located south of Lake Okeechobee in

no-man’s-land of Hendry County. In the middle of the sugar cane fields,

STA-5 consists of four large shallow ponds that occupy an area of eight

square miles.

Birds

and birders flock to water treatment plants. My first experience with

one was the sewage pond at Fort Bliss in El Paso, Texas. It was a green

oasis in the otherwise arid desert, chock full of shorebirds. It

smelled to high heaven! This one has a modest name, Stormwater

Treatment Area Number 5, STA-5 for short, managed by the South Florida

Water Management District, and located south of Lake Okeechobee in

no-man’s-land of Hendry County. In the middle of the sugar cane fields,

STA-5 consists of four large shallow ponds that occupy an area of eight

square miles.  When

walking in wild places, it is best to expect the unexpected.

More often than not, whether searching for a goshawk in the mountains

of New Mexico, the Red-headed Woodpecker in my favorite birding patch

in Illinois, or a Cottonmouth in the wetlands next to my Florida home,

my quest eludes me. Therefore, I keep an open mind and just wait for

each new day’s surprise. By South Florida standards, yesterday

morning was another in a string of unusually cold days. The temperature

was in the low forties, and a brisk breeze blew in from the north.

Insects were inactive in the cold. Tree leaves and grasses were

swaying, making it difficult to detect subtle movements that might

betray small creatures hiding in the foliage. Not a good day for

finding birds and butterflies.

When

walking in wild places, it is best to expect the unexpected.

More often than not, whether searching for a goshawk in the mountains

of New Mexico, the Red-headed Woodpecker in my favorite birding patch

in Illinois, or a Cottonmouth in the wetlands next to my Florida home,

my quest eludes me. Therefore, I keep an open mind and just wait for

each new day’s surprise. By South Florida standards, yesterday

morning was another in a string of unusually cold days. The temperature

was in the low forties, and a brisk breeze blew in from the north.

Insects were inactive in the cold. Tree leaves and grasses were

swaying, making it difficult to detect subtle movements that might

betray small creatures hiding in the foliage. Not a good day for

finding birds and butterflies.  Observers

of our local Bald Eagle nest have noted some interesting

behaviors. These are personal discoveries. They gain insights into the

lives of these magnificent birds, and it matters not that their

findings are not new to science.

Observers

of our local Bald Eagle nest have noted some interesting

behaviors. These are personal discoveries. They gain insights into the

lives of these magnificent birds, and it matters not that their

findings are not new to science.